Food production can go hand in hand with removing CO2 from the atmosphere and fixing it in the soil, and if financial incentives are in place farmers can be encouraged to perform this carbon sequestration. It’s known as “carbon farming” and it has the potential to deliver a new green revolution. But farmers do need to be able to show how much CO2 they are capturing. Data technologies and specific self-learning models (machine learning) will play an important role in this.

A “deep-dive” session organized by the Wageningen startup accelerator StartLife revealed that these smart, self-learning models are already emerging. The session brought together scientists from Wageningen University & Research, representatives from Rabobank and two startups – EnvirometriX and Spatialise – to brainstorm about this topic.

What does carbon farming actually mean? It’s a production method by means of which agricultural businesses maximize CO2 (carbon) sequestration from the atmosphere into the soil. Carbon ends up in crop roots, crop residues (organic matter) in the soil and embedded in healthy soil life.

Carbon farming occurs when the level of carbon sequestration is greater than the degree emitted. But maximizing carbon sequestration does not automatically translate into a big financial return. The idea, therefore, is that farmers ought to be rewarded for the carbon they capture.

Turning emitters into sequestrators

This could be done by providing them with carbon credits that can be traded. Buyers can become CO2-neutral and sellers can turn their sustainable management into a new revenue stream.

“Globally, the food and agriculture sector is a net emitter and, depending on how you calculate it, responsible for 25 to 35 percent of carbon emissions. But it’s also one of the few sectors capable of transitioning from being a net emitter into a net sequestrator. Isn’t that great?” says Kim van der Leeuw at Rabo Carbon Bank, a division of Rabobank which is developing financing based on carbon credits.

This is currently already being done on a voluntary basis. The further development of the carbon credits system now depends on the availability of reliable and practical methods for quantifying how much carbon has been sequestered.

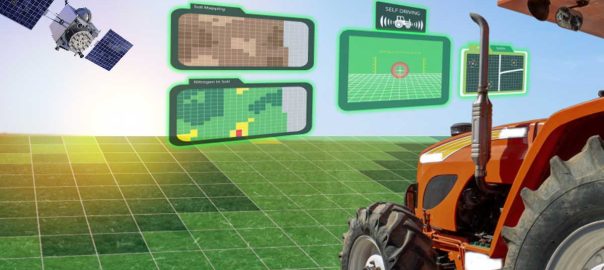

Smart data technology as a catalyst

In theory, this can be done by regularly taking soil samples and analyzing them. But that’s laborious, impractical and expensive. The solution lies in the use of smart data technology. Two startups based in Wageningen – EnvirometriX and Spatialise – are working hard on this. They’re combining geographical data with remote sensing (satellite observations) and local data, such as the results of soil analysis and yield figures. They’re also working on machine-learning models that can measure and analyze carbon sequestration, and do so remotely, continuously and fully automatically.

“The system learns to make connections so that it can eventually come to reliable conclusions based on widely available data, such as satellite images.”

~ Soufiane el Khinifri, Spatialise

Their models are still being developed and need to be fed with as much data as possible to make them more accurate, including satellite images, data on how much carbon has been sequestered in the soil and the agricultural methods being used.

“The system learns to make connections so that it can eventually come to reliable conclusions based on widely available data, such as satellite images. Because it’s a self-learning system, future users won’t need to supply nearly as much data,” says Soufiane el Khinifri, a graduate of Geo-Information Science at Wageningen University.

El Khinifri launched Spatialise last year together with Peter Piontek and fellow student Niels Janssens. One of the areas they’re focusing on is farmers in developing countries.

“Here in the Netherlands, we’re trying to improve the margins for carbon farming, but in developing countries farmers could reap the rewards immediately,” says El Khinifri. “Small-scale farmers in Africa have a relatively low income per hectare. They would really benefit from a carbon- farming premium.”

Optimizing carbon sequestration

Quantifying carbon sequestration in order to reward farmers is not the only potential application. According to Ichsani Wheeler, who was awarded a PhD on this topic, farmers can also use the data to actually increase the extent of carbon sequestration.

Wheeler, originally from Australia, and Tomislav Hengl, from the Netherlands, are the co-founders of EnvirometriX, which helps businesses and other organizations improve their management of natural resources. Their objective is to use smart systems to help farmers with the sustainable management of their operations.

“We want to use machine learning to create a system that recognizes data, combines it and translates it into usable information. The aim is to enable farmers to monitor the progress of their business and use our data to make better management decisions. We want to offer a kind of barometer tool,” she says.

Creating a new green revolution

Carbon farming has the potential to drive a new green revolution.

~ Ichsani Wheeler, EnvirometriX

“Carbon farming has the potential to drive a new green revolution,” says Wheeler. “ The need for it is urgent. We can see a visible decline in soil quality and in ecosystems. They need to be restored. As a society, we need not only a food production system but also ecosystem services, such as clean water, attractive landscapes, biodiversity, etc..”

Carbon sequestration can also be an important indicator for valuing and rewarding these ecosystem services, says research associate Fenny van Egmond, one of the Wageningen researchers who took part in the deep dive. “The economic reality is that intensive, highly productive agricultural systems deliver greater yields per hectare in the short term. If you want farmers to provide ecosystem services, you have to put a revenue model in place.”

“You need each other”

Van Egmond is a research associate in soil sensing at Wageningen Environmental Research and at ISRIC – World Soil Information. According to her, the science – the data research, methods such as machine learning and carbon farming technologies – dovetails nicely with what the startups are doing.

“We’re working toward the same goal. Scientists are researching the impact of different agricultural methods on carbon sequestration as well as the kinds of methods that deliver the best yields across the board. They’re also contributing to the development of new measurement systems, and ways of using and combining other kinds of data available to us. Startups can focus more on the application in a practical product and on the business perspective. An organization like Rabobank has a very specific financial role to play. We all need each other.”

Joined deep dive

That’s exactly why StartLife has brought these different stakeholders together, says Laura Thissen, Operations Director at StartLife. “The participants shared their knowledge with each other and considered the same problem from different perspectives, giving them all new insights into the application of particular methodologies or into data sources they weren’t familiar with. That’s a win. It’s why we bring stakeholders together. It’s so they can learn from each other’s knowledge and experience, and work together on next steps, for example in relation to standardization and data collection from farmers.”

“Collaboration is essential when it comes to a complex issue like measuring carbon sequestration in the soil.”

~ Laura Thissen, StartLife

Niels Snoep, Innovation Manager SME & Corporates at Rabobank, agrees: “Each stakeholder provided added value so that we collectively accelerated. It’s a great example of how open innovation delivers added value, thanks to our partnership with StartLife.”

First payments made to farmers for carbon credits

Shortly after the deep-dive session, Rabo Carbon Bank announced the launch of a pilot in which dairy farmers will be paid for carbon credits. It’s the carbon bank’s first trial on Dutch soil and will last for three years. A pilot aimed at arable farmers has also been launched in the USA.